To Bora-Bora and Back Again:

To Bora-Bora and Back Again:The Story of Armstrong W. Sperry

To Bora-Bora and Back Again:

To Bora-Bora and Back Again:

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS enjoyed the distinction of having his

books illustrated by several critically accepted artists. Among these have been N.

C. Wyeth, Frank E. Schoonover, J. Allen St. John (especially in the early part of

his career), C. E. Monroe, Jr., Robert Abbett, Frank Frazetta and Michael Whelan.

However, one of Burroughs' illustrators managed to produce work, contemporaneously

and for a time, which was more critically acclaimed than his own. And he VMS both

illustrator and writer. During his lifetime, Burroughs received no literary awards,

even though his output was prodigious and his stories beloved by millions at the

peak of his long career. Yet, today, if you were to mention the name of Armstrong

W. Sperry in art or literary circles, even among Burroughs fans and collectors, you

would find it virtually unknown, although he was the winner of the prestigious John

Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to American books for children

in 1941, the New York Herald Tribune Children's Spring Book Festival award for 1944,

and the Boy's Clubs of America Junior Book Award of 1949. In the realm of Burroughs

literature, Sperry had the distinction of designing and illustrating the first Burroughs

book to be published (September 28, 1929) by Metropolitan Books.

EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS enjoyed the distinction of having his

books illustrated by several critically accepted artists. Among these have been N.

C. Wyeth, Frank E. Schoonover, J. Allen St. John (especially in the early part of

his career), C. E. Monroe, Jr., Robert Abbett, Frank Frazetta and Michael Whelan.

However, one of Burroughs' illustrators managed to produce work, contemporaneously

and for a time, which was more critically acclaimed than his own. And he VMS both

illustrator and writer. During his lifetime, Burroughs received no literary awards,

even though his output was prodigious and his stories beloved by millions at the

peak of his long career. Yet, today, if you were to mention the name of Armstrong

W. Sperry in art or literary circles, even among Burroughs fans and collectors, you

would find it virtually unknown, although he was the winner of the prestigious John

Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to American books for children

in 1941, the New York Herald Tribune Children's Spring Book Festival award for 1944,

and the Boy's Clubs of America Junior Book Award of 1949. In the realm of Burroughs

literature, Sperry had the distinction of designing and illustrating the first Burroughs

book to be published (September 28, 1929) by Metropolitan Books.

Armstrong Sperry was born on November 7, 1897 in New Haven, Connecticut to Sereno

Clark Sperry and his wife Nettie. His father was a business executive and his forebears

were among the state's earliest settlers. On one side of the family the men followed

the call of the sea, while those on the other tilled the soil. Throughout most of

his life, Sperry was conscious of these two dichotomous impulses within himself.

He maintained a working farm. in the green hills., of Vermont, but on occasion could

not resist the call of the sea, the sound of breaking surf, or the sight of tall

ships.

As a young boy, Sperry often sat wide-eyed at the feet of his great-grandfather,

Captain Sereno Armstrong while he related stories of hair-raising adventures among

pirates in the China Sea or among the cannibals who lived on lagoon islands rich

with pearls. In particular, he was delighted with stories about a wonderful South

Sea island named Bora-Bora, and he promised himself that, one day, he would sail

there.

But reality soon intruded on his daydreams. His heart may have been in the South

Seas but his parents insisted that he get a proper education. Sperry attended the

Stamford Preparatory School where he spent most of his time drawing pictures and

scribbling stories. His frustrated teachers merely shook their heads in gloomy doubt,

certain that no good would come to any boy who preferred drawing cannibals to solving

the knotty problems of algebra.

After graduating from high school in 1914, Sperry worked for a while doing odd jobs.

It wasn't long before the nation was embroiled in the First World War and he joined

the United States Navy where the spent the year of 1917. Sperry received his first

formal art training when he entered the Yale School of Fine Art in 1918. In 1919

he headed for New York City and was soon enrolled in the Art Students League where

he studied for three years under George Bellows and Luis Mora. He then traveled to

Paris, France in 1922 where he studied at Colorassi's Academy.

On his return to America, Sperry's practical career in illustration began when he

answered an ad for "Help Wanted ... Artist." He was hired and spent a year

working for $25 a week drawing pictures of vacuum cleaners, canned soup and beautiful

blonde women wearing Venida hair nets. Not remarkably, he found himself thinking

of Captain Armstrong, the South Seas, and especially Bora-Bora. Sperry also waxed

nostalgic about a book that had enchanted him in 1919, Frederick O'Brien's WHITE

SHADOWS OF THE SOUTH SEAS which contained 63 alluring black and white photographs.

This memory was what gave him the additional impetus for deciding to quit his job

and sail off to the South Seas. This was before Hollywood had discovered Tahiti or

Dorothy Lamour made the sarong a national commodity! Taking pen in hand, Sperry wrote

a letter to O'Brien requesting information concerning ways and means of sailing to

the South Seas. "And that," remarked Sperry, "was how I came to be

standing on the deck of a copra schooner on a bright sunny June day in 1925, sailing

from Tahiti to Bora-Bora." He had signed on as assistant ethnologist with the

Kaimiloa expedition to the South Pacific.

His first sight of Bora-Bora was everything that Sperry had dreamed it

would be: I saw a single great peak towering 2,000 feet, rising straight up from

the plane of the sea. This peak was buttressed like the walls of an ancient fortress,

and it was made of basalt ... volcanic rock ... which glistened in the sun like amethyst.

There were waterfalls spilling from the clouds and, up in the mountains, the wild

goats were leaping from peak to peak. There was something so fresh about that island

that it seemed as if it had, that very morning, risen up from the floor of the sea

with the spray still shining on it."

His first sight of Bora-Bora was everything that Sperry had dreamed it

would be: I saw a single great peak towering 2,000 feet, rising straight up from

the plane of the sea. This peak was buttressed like the walls of an ancient fortress,

and it was made of basalt ... volcanic rock ... which glistened in the sun like amethyst.

There were waterfalls spilling from the clouds and, up in the mountains, the wild

goats were leaping from peak to peak. There was something so fresh about that island

that it seemed as if it had, that very morning, risen up from the floor of the sea

with the spray still shining on it."

Sperry spent several months living on this primitive enchanted island. While he was

there the islands were experiencing a boom in the vanilla bean crop. Suddenly a blight

struck all of the other islands except Bora-Bora, which soon took on the aspect of

a boom town similar to that of the Gold Rush days in California. The islanders found

themselves millionaires almost overnight; movie palaces sprang up, the men bought

automobiles, and the women the latest Paris gowns. with these riches also came theft

and murder. The old chief, Opu Nui, observed sadly that the people had lost their

initiative, their native customs and traditional ways of living. Suddenly the vanilla

boom was over ... new vines had replaced the stricken ones on the other islands.

And the season of storms had arrived. One afternoon a great hurricane struck Bora-Bora

and the newly made millionaire's houses and possessions were destroyed; and the people,

fleeing its fury, took refuge in the mountains. Soon they faced famine and privation,

compounded by the fact that they had grown soft from easy living. Led by the old

chief, they rallied and were able to win a victory, not so much over a natural disaster

but as a more personal victory over themselves...

Sperry said: "The thing which remains with me most vividly from those months

on Bora-Bora, stronger than the manifold charms of the island, is the remembrance

of the great courage with which that little band of Polynesians faced the destruction

of their world and faced it down, and stooped, only to rebuild."

Upon his return to New York Sperry settled back into his work as a freelance illustrator

working for several accounts I in the field of commercial advertising or illustration.

His brush and ink or pen work somewhat resembles old fashioned wood block prints.

His paintings are more in the mold of N. C. Wyeth ... boldly masculine and colorful.

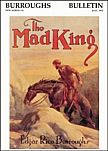

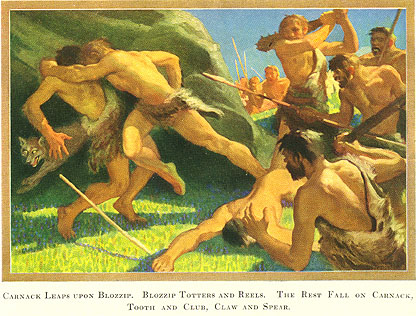

A book found on some Burroughs collector's shelves, CARNAK THE LIFEBRINGER "The

Story of a Dawn Man Told by Himself" interpreted by Oliver Marble Gale, published

by the William H. Wise Company, New York, 1928, contains some of Sperry's most exciting

illustrations: a color frontispiece and three full color plates. These run the gamut

from placid forest scenes to bone crunching battles. The color frontispiece also

appears on the dust wrapper. Sadly, few books are known which contain his illustrations

prior to the advent of his own writing career.

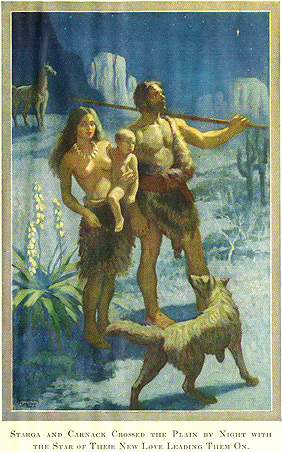

The next year, Sperry illustrated TARZAN AND THE LOST EMPIRE for Metropolitan

Books. There is a possibility that Sperry was working for the United Features Syndicate

along with Rex Maxon, Paul Berdanier, and Hugh Hutton, since they were working in

Metropolitan's art department at the same time (Maxon excepted). It can be assumed

that the need to keep production costs down explains why Sperry was commissioned

only to do the dust wrapper and a frontispiece for TARZAN AND THE LOST EMPIRE. The

dust wrapper features Tarzan, clasping a sword and standing in the center of the

arena at Castra Sanguinarius. It is done in Sperry's woodcut style with color being

added at the printer's. The back of the dust wrapper features a small portrait of

ERB and various African animals, all done in the woodcut manner. This portrait of

Burroughs and the animals was used on the back of the Grosset & Dunlap reprint

dust wrappers after 1940, and on the back of most of the Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

1948 reprints. The frontispiece (pictured below), though black and white, is powerful

and ably displays Sperry's command of design and anatomy. This was the first book

to depict Tarzan wearing an over-the-shoulder leopard skin, no doubt inspired by

Frank Hoban's illustrations for BLUE BOOK magazine. It was also the first book, after

TARZAN OF THE APES, to be illustrated by an artist other than J. Allen St. John.

The next year, Sperry illustrated TARZAN AND THE LOST EMPIRE for Metropolitan

Books. There is a possibility that Sperry was working for the United Features Syndicate

along with Rex Maxon, Paul Berdanier, and Hugh Hutton, since they were working in

Metropolitan's art department at the same time (Maxon excepted). It can be assumed

that the need to keep production costs down explains why Sperry was commissioned

only to do the dust wrapper and a frontispiece for TARZAN AND THE LOST EMPIRE. The

dust wrapper features Tarzan, clasping a sword and standing in the center of the

arena at Castra Sanguinarius. It is done in Sperry's woodcut style with color being

added at the printer's. The back of the dust wrapper features a small portrait of

ERB and various African animals, all done in the woodcut manner. This portrait of

Burroughs and the animals was used on the back of the Grosset & Dunlap reprint

dust wrappers after 1940, and on the back of most of the Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

1948 reprints. The frontispiece (pictured below), though black and white, is powerful

and ably displays Sperry's command of design and anatomy. This was the first book

to depict Tarzan wearing an over-the-shoulder leopard skin, no doubt inspired by

Frank Hoban's illustrations for BLUE BOOK magazine. It was also the first book, after

TARZAN OF THE APES, to be illustrated by an artist other than J. Allen St. John.

Three years later, Sperry began his career as a writer and illustrator of children's

books. He had long desired to write of the South Seas, using his own experiences

to lend realism to these stories. Children seemed the logical audience for the wealth

of material he had acquired in the South Seas, and his background as an illustrator

was perfect for the pairing of words and pictures. His first book, ONE DAY WITH MANU,

is a tale of everyday life on Bora-Bora, and was published in 1933 by Winston, Philadelphia.

An immediate success, it was followed by ONE DAY WITH JAMBI in Sumatra in 1934, same

publisher. His next book, ONE DAY WITH TUKTU, AN ESKIMO BOY (1935) was based solely

on research rather than first hand experience, and Sperry found such a book more

difficult to do. Next followed a sea story, ALL SAIL SET (1936), the story of the

clipper ship FIying Cloud. A story of the west, WAGONS WESTWARD (1936), was based

on his automobile trip over the old Santa Fe Trail. Traveling the southwest opened

up a whole new area for him to write about, and out of that experience came LITTLE

EAGLE, A NAVAJO BOY (1938). Then came another South Sea book, LOST LAGOON (1939).

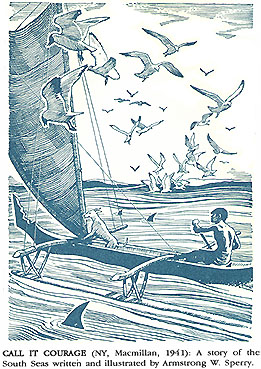

In 1941 Macmillan published CALL IT COURAGE. Hardly more than novella length,

this story about a Polynesian youth, Mafatu, nevertheless achieves an almost mythopoeic

quality which fully justifies its presentation as a story which the Polynesians "even

today ... sing in their chants and tell over the evening fire." Ever since a

terrible experience as a child of three in a hurricane which takes his mother's life,

Mafatu has been afraid of the sea.

Shamed by his people's contempt, Mafatu sets out in a canoe, accompanied only by

Uri, a nondescript yellow dog, and Kivi, a lamed albatross, "to face the thing

he feared most." Surviving a violent storm. which carries away his mast, oar,

and all of his gear, he helplessly drifts on a mysterious ocean current, finally

coming to rest on a mountainous island, presumably one of the Solomons. Here he discovers

a sacred place guarded by a hideous idol to whom the cannibals from a neighboring

island periodically make human sacrifices, and removes from it a spear which he needs

as a weapon. While on the island he proves his courage and skill by making tools

to fish with and a raft to fish from; by killing a shark, a wild boar, and a giant

octopus, and by building a canoe from a tamanu tree. On the day that his preparations

are completed for his journey home, the cannibals return and he narrowly escapes

in his canoe, pursued by the savages who paddle vengefully after him for a day and

a night. For long arduous days and nights he endures the journey back to his own

island, against the ocean current and a fitful wind, finally to arrive triumphantly

with a necklace of boar's teeth and a splendid spear ... which vindicates him in

the eyes of the Chief, his father. Armstrong Sperry superbly conjures up the setting,

both of the sea and of the two contrasting islands, as well as offering a detailed

account of the skills by which Polynesians survive. The archetypal character of the

story ... a boy's testing of himself which takes on the nature of an initiation into

manhood ... held strong appeal.

This

was Sperry's eighth book for children and, in June, 1941, at a meeting of the American

Library Association in Boston, he was presented with the John Newbery Medal. In his

acceptance speech, Sperry said:

This

was Sperry's eighth book for children and, in June, 1941, at a meeting of the American

Library Association in Boston, he was presented with the John Newbery Medal. In his

acceptance speech, Sperry said:

"CALL IT COURAGE meant a great deal to me in the writing but I had no idea that the response to the book would be so wide among children. I had feared that the concept of spiritual courage might be too adult for the age group such a book would reach, and that young people would find it less thrilling than the physical courage which battles pirates unconcerned or outstares the crouching lion. But it seems I was wrong ... which only serves to prove that children have imagination enough to grasp any idea which you present to them with honesty and without patronage."

Doris Patee wrote of the book's style: "In Armstrong Sperry's beautiful prose

the tale moves smoothly and rapidly like a native chant, and its music rises and

falls like the billows of the sea in its setting. Storytellers who have used the

story often find children entranced not only by the story itself but by the cadence

and rhythm of the language."

Two other books by Sperry, LOST LAGOON and HULL-DOWN FOR ACTION, have a similar geographical

setting no less vividly portrayed. However, in each, the plot and characterization,

belonging to the period before and just after Pearl Harbor, are more standard boys'

adventure store fare. The books are exciting but the villains, the inscrutable Jap,

the arrogant Nazi, are no more than conventional stereotypes.

Two special qualifications made Armstrong Sperry outstanding among the notable writers

of children's books of that time. One was his unusual and authentic South Sea subject

matter, and the other was that he was both a writer and artist. Helen Follett, whose

STARS TO STEER BY (1934) and HOUSE AFIRE! (1941) were illustrated by Sperry, once

said to him: "The astonishing thing about you is not that you're a fine artist,

or a fine writer, but that you are both!" Sperry replied that being both was

a "lot of hard work" but also "lots of fun."

Sperry stated: "I was an illustrator for ten years before becoming a professional

writer. Combining the two media led me into the field of children's books. From the

beginning of my career it has been my conviction that no writer should ever write

down to children. He should tell his story clearly, in a supple prose that leaves

his reader, young or old, wondering What happens next?"'

Armstrong W. Sperry died on April 28, 1976 in Hanover, New Hampshire, at the age

of 78. He wrote and illustrated over twenty-five books and illustrated numerous others

for a variety of authors. At the time of his death, he was survived by his wife,

Margaret Roberts[on] Sperry, whom he had married in 1930; a son, John; a daughter,

Susan Bums; and six grandchildren and a brother.